The Growing Disaster of Displacement

Disasters caused by natural hazards is a

recurring phenomenon in our recorded history and has become even more of a topic

of discussion in the 21st century.

The debate on climate change and whether or not we have been

experiencing more natural disasters than ever before is an issue of major

importance. While some believe that these

natural disasters are cyclical and have little to do with “man-made climate

change”, perhaps supporting this theory because of personal interests, the majority

of climate change scientists suggest otherwise.

Regarding storms, flooding, droughts, wildfires, heat/cold waves, earthquakes,

volcanoes, coastal erosion, landslides, and avalanches, experts, politicians, and

the public alike are weighing in on the trends.

While the increase in general of natural

disasters may be a matter of dissent, the impact of these occurrences on the health

and wellbeing of the population affected is something that is not up for

debate. In 2010 the earthquake in Haiti displaced an estimated number of 1.2

million people, in 2011 the east African drought in Somalia 1.46 million, and in

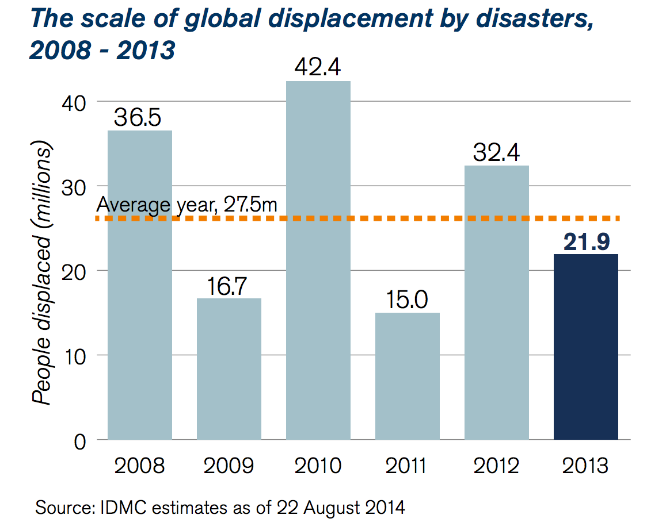

2013 Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines displaced over 5 million (USAID). According to one of the latest reports put

out by the International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) almost 22

million people globally were displaced throughout 19 different countries in

2013, which was almost three times more than were displaced by conflict and

violence.

While the increase in general of natural

disasters may be a matter of dissent, the impact of these occurrences on the health

and wellbeing of the population affected is something that is not up for

debate. In 2010 the earthquake in Haiti displaced an estimated number of 1.2

million people, in 2011 the east African drought in Somalia 1.46 million, and in

2013 Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines displaced over 5 million (USAID). According to one of the latest reports put

out by the International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) almost 22

million people globally were displaced throughout 19 different countries in

2013, which was almost three times more than were displaced by conflict and

violence. What does it mean to be displaced? The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees defines displacement as "the forced movement of people from their locality or environment and occupational activities." Depending on the natural disaster, populations may be evacuated (earthquakes, storms) or individuals may relocate over time as they decide that their communities are no longer inhabitable (droughts). Displaced individuals may flee across international borders (refugees) or remain within their country of residence (internally displaced). Displacement can range from a couple of weeks to years, temporary or prolonged. Their travel may be to the community next door or reach far distances. Individuals can become scattered over rural land or migrate to large cities. They may seek relief individually or become concentrated within displacement camps. It can be a one-time occurrence or repeated and frequent. The range of possibilities in movement for displaced individuals makes it difficult to design and manage adequate relief interventions that address specific population needs. However, displacement in and of itself leaves populations homeless, impoverished, with a lack of access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation, and vulnerable to disease, malnutrition, discrimination, and violence.

The main problem in using global statistics

on the number of displaced persons by natural disasters is that many fail to capture

displacement past the year in which it started, and for those that do, the very

act of defining when someone is no longer considered displaced causes

confusion. The Inter-Agency Standing

Committee, a forum of UN and non-UN humanitarian agencies, has laid out a

framework for internally displaced individuals (IDPs) stating that a “durable

solution” to their displacement can be achieved when they “no longer have any

specific assistance and protection needs that are linked to their displacement

and can enjoy their human rights without discrimination on account of their

displacement.”

The main problem in using global statistics

on the number of displaced persons by natural disasters is that many fail to capture

displacement past the year in which it started, and for those that do, the very

act of defining when someone is no longer considered displaced causes

confusion. The Inter-Agency Standing

Committee, a forum of UN and non-UN humanitarian agencies, has laid out a

framework for internally displaced individuals (IDPs) stating that a “durable

solution” to their displacement can be achieved when they “no longer have any

specific assistance and protection needs that are linked to their displacement

and can enjoy their human rights without discrimination on account of their

displacement.”

The difficulty with this definition is that

“assistance” and “needs” linked with displacement are much more complicated

than just “protection” and “enjoying human rights without discrimination”. Displacement is a complex situation that goes

beyond management of the acute needs of these individuals. It requires a definition with a long-term focus

because the effects are long-term.

According to the Brookings Institution 2014 report on Supporting Durable Solutions to Urban,

Post-Disaster Displacement: Challenges and Opportunities in Haiti, “of

those who were displaced in 2010, 74% continue to identify themselves as

displaced, even though they were not currently resident in a camp, underscoring

that displacement is not limited to camp settings, and the long-term nature of

the challenge of rebuilding “home” in the aftermath of disaster.” Less than just one year later, on the 5th

anniversary of the earthquake, the International Organization for Migration

(IOM) claimed that they saw a 94 percent decrease in the number of Haitians

displaced.

It is clear from reports, such as

that from the IOM, that major international organizations are quick to count “successes”

and slow to understand the reality of the long-term consequences of these

disasters. The ramifications of such contradictory

reports can have disastrous effects on future aid and attention to the development

of communities after the wake of a natural disaster. There needs to be better post-monitoring and studies

that focus on the effects not just directly afterwards, but rather throughout

the long-term recovery from these natural disasters. For instance, why do individuals consider themselves

displaced long after having found housing or leaving camps? Have they seen a decline in access to essential

services once they become reestablished?

At what point do they feel safe again? What are the long-term mental

effects? Are they stable enough to find

sustainable employment?

|

| Joe Raedle/Getty Images |

Global

Estimates 2014 People Displaced by Disasters. Internal Displacement Monitoring

Centre. 2014. Available at http://www.internal-displacement.org.

Supporting

Durable Solutions to Urban, Post-Disaster Displacement: Challenges and

Opportunities in Haiti. The Brookings Institute. 2014. Available at http://www.brookings.edu.

No comments:

Post a Comment